SitRep - 2025/08/16

The fiction that Russia is negotiating from a position of strength in Alaska.

Ukraine leads the free world now.

That is the clear takeaway of yesterday’s Trump-Putin summit. The United States in 2025 is proving itself too fickle, selfish, and ill-informed of history to help ameliorate suffering and guide the world towards a better future.

Reporters, like Constant Meheut writing for the New York Times, for major outlets have characterized Russia as negotiating from a position of strength at the Alaska Summit. This is a gross mischaracterization of both the gains and costs incurred by Russian armed forces this year.

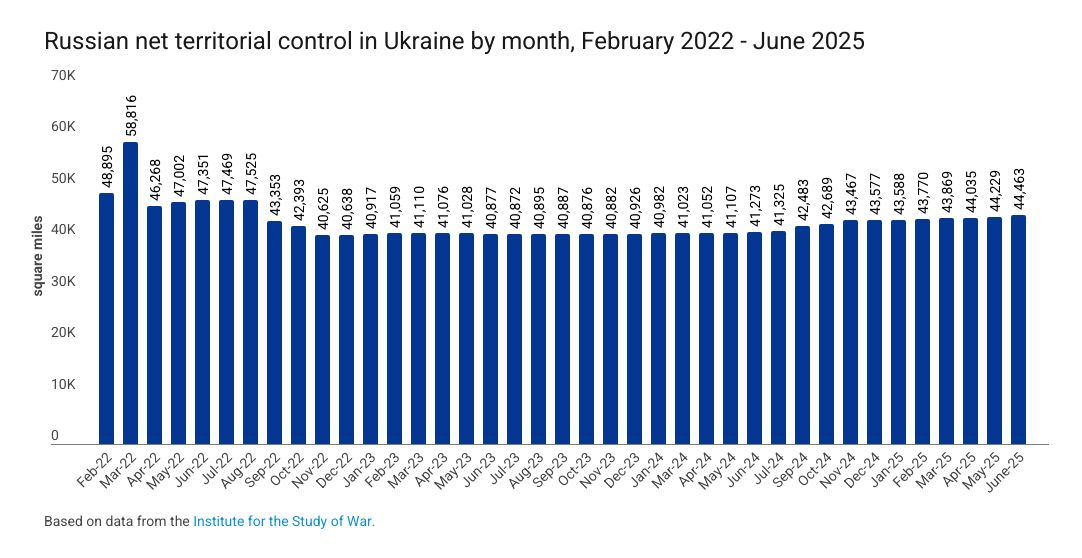

The think-tank Russia Matters has tallied the number of square miles seized and occupied by Russia each month since the beginning of this war.

It is worth noting that Russian forces still occupy less territory than they did at the beginning of March 2022. Recent gains are even more paltry. During the first half of 2025, Russian forces have seized less than 1,000 square miles of Ukrainian territory — smaller than the smallest US state of Rhode Island (1045 sq mi).

Another way to put it is that in November 2022 — after Ukrainian counterattacks push Russian forces from near Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Kherson oblasts — Russian controlled ~18% of all Ukrainian territory. As of mid-2025, Russia now controls ~20% of Ukrainian territory, if one rounds generously. Given that UK intelligence estimates total Russian casualties in this war at over one million, one can safely reason that the 1-2% of extra Ukrainian land cost the health of approximately 500,000-750,000 Russians.

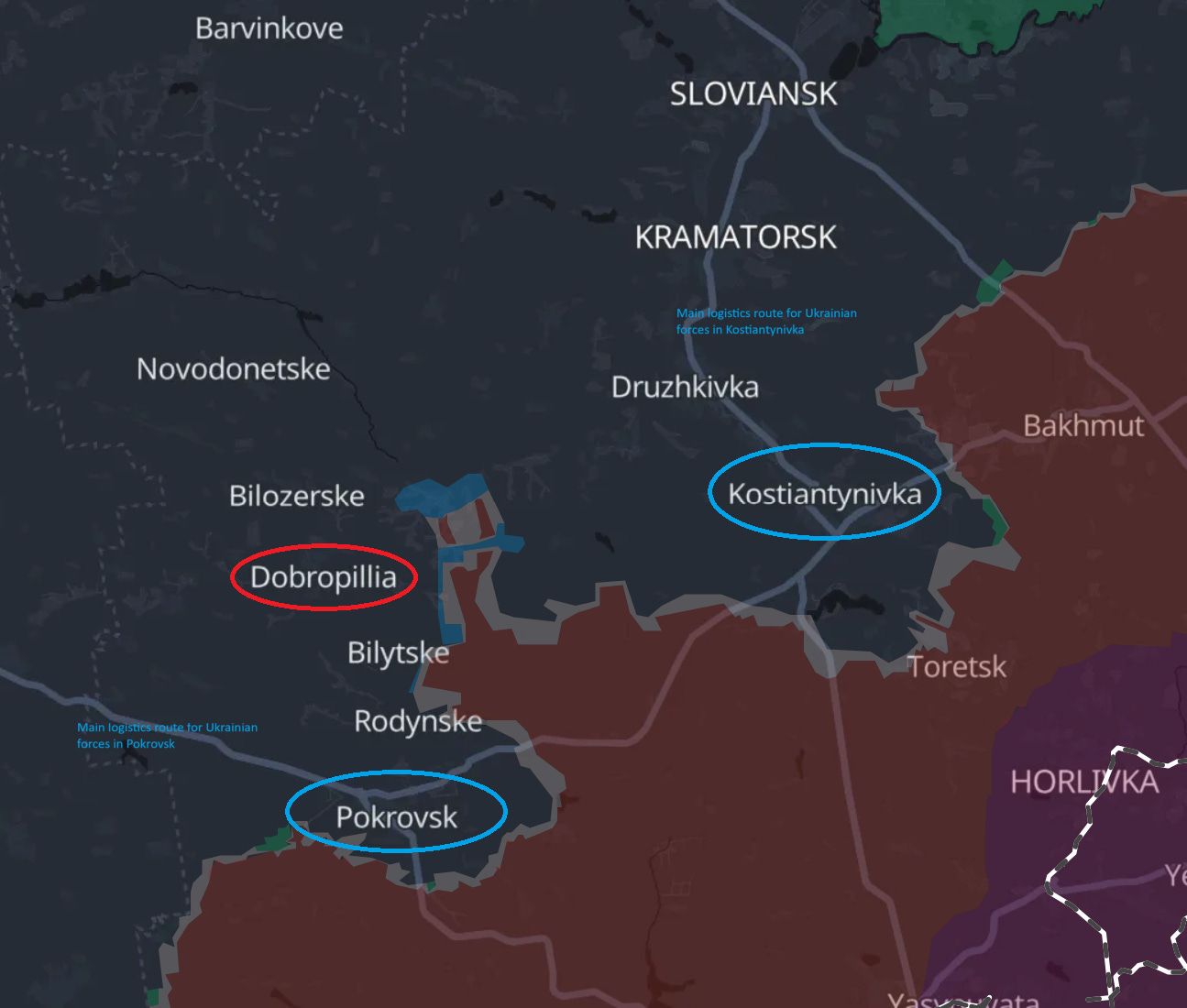

But Meheut is likely referring specifically to the recent Russian infiltration near Dobropillia.

The effort to take both Pokrovsk and Kostiantynivka has been a years-long process for Russia. Since taking Bakhmut in May 2023, Russian forces have been fighting to seize Chasiv Yar and Toretsk, control of which are prerequisite to attacking Kostianynivka. Similarly, throughout much of 2024, Russia focused on advancing from the Avdiivka area to reach the environs of Pokrovsk.

Last week, three groups of Russian soldiers snuck past Ukrainian defensive positions west of Kostiantynivka and east of Pokrovsk, “driving a wedge” between Ukrainian defenders, as Meheut put it. This ignores that the infiltration did not threaten either of the major Ukrainian resupply routes in the area, that the area is not particularly tactically important to the defense of either city, and that Ukraine’s 93rd Brigade has spent the last week effectively clearing the area of Russian infiltrators.

The idea that these Russian diversionary-reconnaisance groups (DRG) are major threat to Ukraine’s ability to hold Pokrovsk or Kostiantynivka has about as much basis in the real world as the idea that Trump will facilitate a stable peace in Alaska.

Instead of negotiating from a position of strength, I would argue Russia is negotiating without the advantage of time. Russia has leaned into large financial incentives to generate new recruits for its war effort.

First termed “deathonomics” by Vladislav Inozemtsev, Russia has created perverse financial incentives that few Russian men in the hinterlands of Siberia can afford to pass up.

Russian economist Vladislav Inozemtsev calculates that the family of a 35-year-old man who fights for a year and is then killed on the battlefield would receive around 14.5 million rubles, equivalent to $150,000, from his soldier’s salary and death compensation. That is more than he would have earned cumulatively working as a civilian until the age of 60 in some regions. Families are eligible for other bonuses and insurance payouts, too.

“Going to the front and being killed a year later is economically more profitable than a man’s further life,” Inozemtsev said, a phenomenon he calls “deathonomics.”

The economic stimulus provided to a family of a killed or wounded is life-changing, often allowing families to achieve a measure of wealth that could never be attained otherwise.

But the effect of these massive financial incentives are becoming a major drain on Russia’s economy, one that increases with each Russian killed or maimed on the battlefield. As Re: Russia, an analytical group of Russian dissidents, writes:

If the same rate of losses is maintained and from replenishment in the second half of the year, annual [personnel] costs will exceed 4 trillion rubles. This amount, equivalent to 2% of Russian GDP, 9.5% of this year’s federal budget expenditure and 5.5% of the consolidated budget expenditures of last year….

In other words, without even accounting for spending on all the other exorbitant costs associated with war-fighting — the price of ammunition production, drone and EW innovation, etc. — the payouts for signing military contracts and payouts to the families of dead and wounded are set to reach 2% of Russia’s entire GDP.

High profile Russian commanders — including Yevgeny Prigozhin, whose Wagner Group played a pivotal role in capturing Bakhmut — have argued that Russia needed to make use of its authoritarian political structure to conscript large numbers of Russians for the war effort. Given the complete monopoly on state violence enjoyed by the Russian government, the Kremlin could easily forced Russian to serve in the armed forces at a fraction of the cost incurred by “deathonomics”.

Yet, concerned about the political fallout of full mobilization, Putin has chosen to mortgage the future of the Russian economy to sustain a war effort that has struggles to seize even a full percentage of Ukraine’s landmass each year.

As these farcical peace talks continue between Ukraine and Russia, Putin will continue to pretend that Russia has the upper-hand on the battlefield. But his greatest achievement in more than three years of war has been to transform the Russian economy into a Ponzi scheme. He remains convinced that a sweeping Russian victory is imminent. Trump, for his part, will be eagerly posturing himself as a candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize.

But Zelensky, armed with increasing evidence that Ukraine will be able to sustain its war effort for longer than Russia, is likely to be the only one negotiating from a position of reality.

Thanks, Alex. You might also note that Russia controls less of Russia today than it did in 2022. Even if it’s only a few square miles in Kursk and Belgorod, the fact remains: in 2022 Russia controlled 100% of its homeland. Now it doesn’t. You could even add the steady erosion of Russian influence abroad since 2022